I once read a columnist who described green curry as a dish that’s been ‘thoroughly mangled.’ I think that’s a harsh but accurate observation. Part of the problem, I think, is the Internet- both blessing and curse- has democratised the art of recipe writing. I suppose this is both good and bad. Good because there are some highly talented people out there whose content and creativity we are lucky to have access to. Bad because democratisation, in this unique case, floods the system; it overwhelms us with so much noise - myriad voices; myriad recipes; myriad opinions, insofar that important things like provenance, culture and tradition are obfuscated amidst the backdrop of the endless void that is the internet.

I’m not saying that creativity and personal interpretation should be discouraged. Food, like everything, is in flux. If cuisine was fettered by the shackles of tradition, life would be dull. What I am saying though, is if everyone is an authority, no one is an authority. Abundance has a habit of diminishing value, and so it is the case with food recipes. Google ‘Green curry recipe’ and you’ll get a bounty of results. Most offer distorted adaptations that retain little resemblance to the real thing. Most people, I think, understandably don’t really care. They’re happy to run their eyes over a few recipes and choose what they like. For them, the internet and the accessibility that comes with it, is a boon.

There are others, I am sure, who want the real deal. They’re interested in provenance and tradition; they want to know how things were done at the beginning; they believe that culture is the most reliable creator; they think knowledge and familiarity are requisite precursors to creative license. For my sins, I am one of these people.

Neither group is right or wrong. I really believe that. It’s a matter of preference. Most of everyone I know and love is in the ‘I don’t really care camp’ - they optimise for convenience, timeliness and taste. It’s hard to do anything contrary in today’s modern world.

That being said, for those of you who fall near the latter camp, this post is my feeble attempt at providing a Western perspective on a dish that seems to have lost its place in this day and age.

Green Curry - An Overview

Green curry is a dish originating from Thailand’s central plains. It uses floral fresh green chillies in the paste, which give it its quintessential colour. While there are no hard and fast rules for green curry, there are some common patterns. Chicken, fish, or beef are typical proteins. There tends to be one vegetable to accompany the protein - Thai eggplants, baby corn, and heart of palm are common.

The curry paste varies on the cook and the protein but elemental features include Thai green chillies, lemongrass, galangal, coriander root, lime zest, shallot, garlic and shrimp paste. Dried spices can vary again depending on the protein, but white pepper, coriander seed, and cumin are typical inclusions. Fresh turmeric and grachai are less common additions but can be used, respectively, for colour or to deodorise specific ingredients. I almost always use fresh turmeric as it gives the dish a beautiful hue of vibrant green.

The curry paste tends to be fried in split coconut cream (more on that later), but I have seen versions of the dish where the paste is simmered in thickened cream and more so boiled. Never (at least in my experience) is the paste fried in vegetable oil.

Green curry lies on the thin end of the spectrum when it comes to coconut-based Thai curries. It is more akin to a soup (in terms of its viscosity) and not like the thick, sludgy curries we are sometimes served here in the West.

Green Curry with Fish Balls (Gaeng Kiew Wan Luuk Chin Pla): A Recipe

The recipe I’m sharing today contains fish balls as the protein. It is common throughout curry stalls in Bangkok. The fish balls are made from minced fish, flavoured with garlic, coriander root and white pepper - seasoned with fish sauce and sugar. They are utterly delicious.

Equipment

Below are some notes on required equipment (beyond basic items like knives, spatulas etc.)

Must Have

Blender (for blending the coconut to make milk)

Something heavy to break open the coconut (a heavy chef’s knife works, as does a pestle, as does a hammer)

A clean tea towel, muslin cloth or chinois (for straining the coconut cream/milk)

Recommend you Have

Mortar & Pestle

Ingredients (serves 2-4)

Curry Paste

Green birdseye chillies, chopped, 3 tbs1

Lemongrass, chopped, 2 tbs

Galangal, chopped, 1 tbs

Fresh turmeric, chopped, 1 tsp

Coriander roots, chopped, 3 tbs (substitute: 5 tbs of chopped coriander stem)

Makrut Lime Zest, 1 tsp 2 (substitute: normal lime zest)

Thai shallot, chopped, 3 tbs (substitute: French eschalot or red onion)

Whole White Peppercorns, 8

Coriander Seeds, 1/2 tsp

Cumin Seeds, 1/4 tsp

Shrimp Paste, 1 tsp

Fish Balls

Firm fleshed fish fillets, skinned (eg. Gurnard, Trout, Hake, Pollock) 200g

Coriander roots, 3 (substitute 4 tbs chopped coriander stem)

Garlic, 2 cloves

Ginger, 1/2 inch

Whole white peppercorns, 4

Tapioca flour, 1.5 tbs (optional)

Fish sauce, 2 tbs

Sugar, 1 tsp

Everything Else

Coconuts, 33

Long Red Chillies, thinly slices or julienned, 1 tbs

Fresh makrut lime leaves, julienned, 1 tbs (subsitute: frozen makrut lime leaves)

Thai Eggplants, 4, quartered

Fish Sauce, to taste

Thai Basil, palmful of leaves

There are a lot of unique ingredients in the above list. Below are some suggestions of places within London that should offer every ingredient (save for fish and coconuts). If you’re outside of London many online Thai shops will deliver anywhere in the UK. Raan-nuch.co.uk is one I use regularly.

Farang Larder, Stoke Newington

Khun Ya Thai Supermarket, Bermondsey

Raya Grocery, Borough Market

New Loon Moon, Chinatown

Long Dan, Elephant & Castle | Shoreditch | Hackney

Starnight, Hackney

As a general rule of thumb, I go to any of the above grocers to source my lemongrass, galangal, shallot, fish sauce, coriander root, lime leaves, Thai eggplants. I go to a good fishmonger for the fish. And I get my coconuts from Morrisons Online (seriously… see footnote).

Step 1: Make the Paste

Set a pan to medium heat, do not add oil. First, add the coriander seeds and roast, slowly stirring for a few minutes until you can smell their fragrance. Remove and set aside. Do the same for the cumin seeds, they will cook a little faster than the coriander. Combine your roasted cumin and coriander seeds with your white peppercorns, add them to your mortar and pestle (or better still an electric spice grinder) and grind them into a fine powder. Set aside.

Add paste ingredients in the following order, pounding each individually until completely pulverised: chillies, lemongrass, galangal, lime zest, coriander root, shallot, garlic, and shrimp paste.

Add spice mix and mix together until the paste is homogenous i.e. there are no splotchy concentrations of shrimp paste or spice mix.

Shortcut

Make the spice mix as suggested above. Then add all other ingredients (+the spice mix) into a food processor and process until a paste is formed.

Step 2: Make the Fish Balls

Fillet your fish. Debone it. Remove the skin. Throw in a food processor and process until a sort of fish paste is achieved. NB - you can also hand mince with a cleaver but I think a food processor is easier and renders better results.

In your mortar and pestle grind the white pepper into a powder. Add ginger, garlic, and coriander root and pound until a coarse paste is achieved (you can pound them all together, no need to pound them individually).

Add the ginger-garlic paste to the fish mixture, add tapioca starch, add fish sauce and sugar and mix well with your hands or a spatula. Then, take the whole mixture; pick it up and throw it onto a hard surface multiple times. This slapping aerates the mixture and makes the texture more desirable. Test the seasoning by taking a small portion and poaching it in boiling water. Adjust seasoning as necessary.

Once happy with the seasoning, roll fish balls by taking a small portion of the mixture and rolling it into a spherical shape between your two palms. Aim for balls that are around 2.5cm - 3cm in diameter.

Shortcut

Get your fishmonger to fillet, bone and skin your fish to save you the hassle.

Step 3: Make the Coconut Cream

See the below video for a visual guide. One thing to note - you do not need to peel the coconuts as I have, leaving the skin on doesn’t affect the colour or taste noticeably.

The process is straightforward and as follows.

Break open your coconuts —> This is easily done using a pestle or the back of a cleaver. If using a pestle, try to hit the coconut all over - top, bottom, middle- so that it breaks into multiple pieces as opposed to two big halves. The reason for this is that it’s very hard to execute step 2 with two big halves.

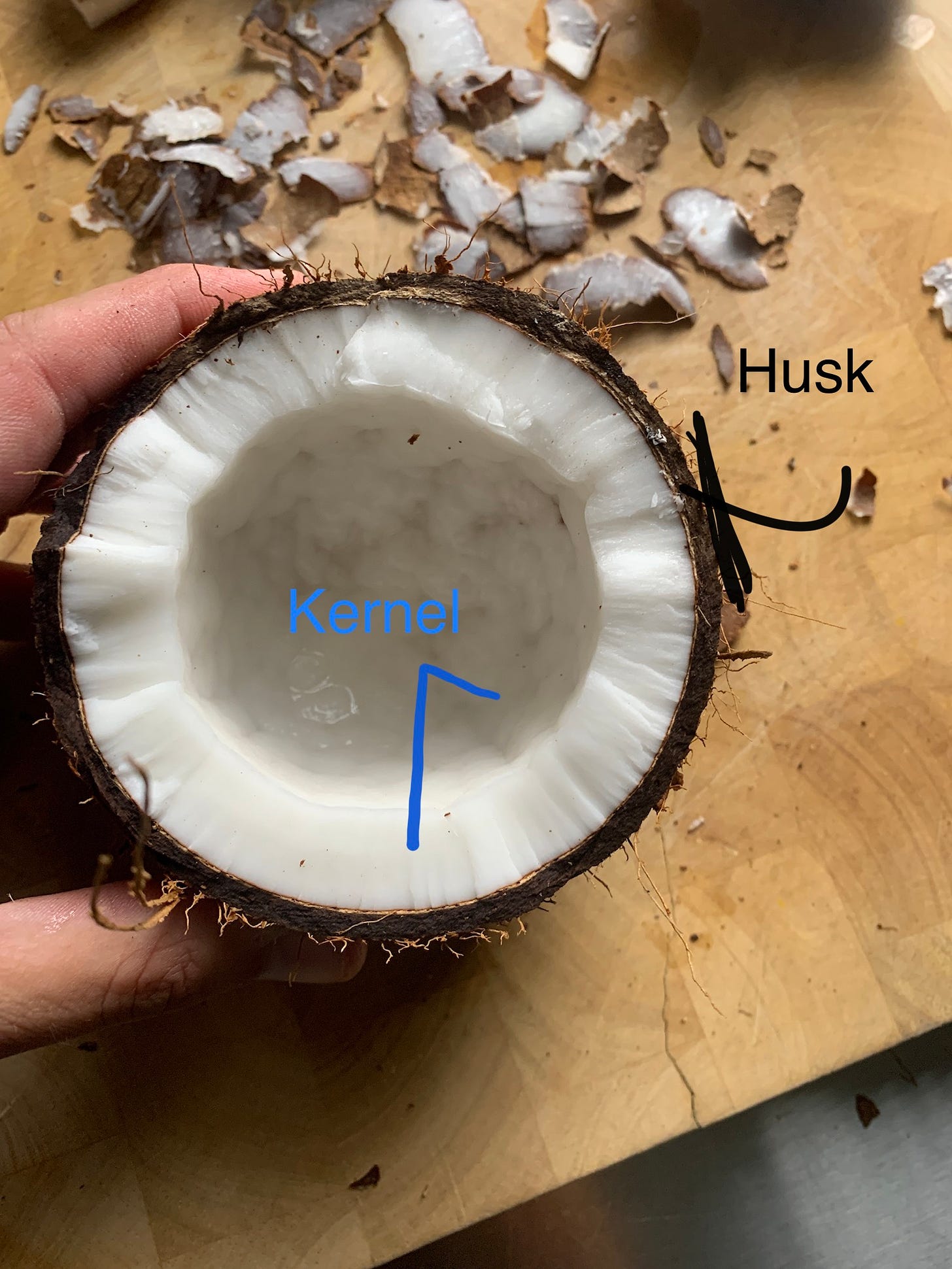

Remove the kernel from the hard exterior —> You should notice two distinct layers of the coconut: the hard outer husk (exocarp) and the softer inner kernel. The two are stuck strongly together. Separating the two is the trickiest part of this process. I do it by wrapping a dull table knife in a teatowel (so if my hand slips I minimise the risk of cutting myself on the albeit dull-ish edge); inserting the point of the knife into the small gap between the husk and the kernel, then prizing the kernel away from the husk. Takes a bit of practice but once you’ve made coconut milk a few times it gets easier every time.

Cut the kernel into chunks —> no need to be precise here. Just cut them into similar-sized chunks that will fit into the blender.

Blend —> Add coconut chunks to your blender. Cover with hot water (no need to be precise regarding temperature, as long as it’s hot but not boiling it will be fine). Blend for a long time - 1-2 minutes. It might be worth doing this in stages so your blender doesn’t overheat.

Strain —> Strain and press into a container through either a chinois, a clean tea towel or a muslin cloth.

Separate the cream —> Set aside the strained mixture in the refrigerator for at least 25 minutes. After that time the cream will rise to the top (fat weighs less than water). Take a large spoon and do your best to spoon the cream out, spoonful by spoonful into a separate vessel. No matter how good you are at spooning the cream out, you are bound to mix some of the cream back into the water. As such, after you’ve spooned as much fat out as possible you will be left with one container of concentrated coconut cream (the good stuff), and a leftover mixture of water and remnant coconut cream. I use this leftover mixture as my coconut milk. Alternatively, you can make milk by reblending the pulp one more time and repeating the straining process. This will render slightly thicker milk but I don’t think it’s necessary for this dish.

Shortcut

I’m guessing this will be the most widely used shortcut, and for good reason - making coconut cream is a hard slog. If you’re going to go down the store-bought route - I think it is best to avoid anything tinned and instead opt for a boxed variety like Chaokoh brand boxed milk (you can sometimes find it on Amazon), otherwise, speciality online Asian grocers stock it. The reason I’m suggesting using this brand specifically is that it is one of the only brands (that I can find here in the UK) that does not contain emulsifiers or stabilisers (I think) - both of which can make ‘cracking the cream’ (see step 4) problematic. That said, back in the day I have managed to crack cream with tinned stuff - but its a bit hit or miss. If in doubt - just use whatever you can get access to.

Step 4: Make the Curry

First, poach the fish balls in boiling water for a few minutes until done then set aside.

Next, crack the cream. Coconut cream is a solution of fat, water, and solids (coconut meat). Cracking the cream refers to the process of separating the fat from the solids to form an oily mixture that serves as a medium to fry the curry paste. Frying curry paste in cracked coconut cream results in much better-tasting curries than frying the paste in seed oil. I remember the first time I made a curry with this important step - I was blown away by how amazing the end result was.

To crack the cream, simply boil the cream until you notice a clear oil/fat has emerged with distinct little curds bubbling away. See GIF below.

Next fry the paste in the cracked cream for about 5 minutes, stirring constantly to avoid it burning. Once the paste has lost its raw aroma it is done.

Next, add coconut milk and bring to a boil. Season with fish sauce, taste and adjust accordingly. Some recipes/cooks will season with sugar, others omit sugar and rely on the natural sweetness of the coconut cream. I tend to favour salty and sour flavour profiles so I prefer to make this curry without sugar, letting the coconut cream round out the dish.

Finally, add eggplants and simmer for a few minutes until cooked. Then add red chillies, shredded lime leaves, fish balls and Thai basil. Stir a couple of times and you’re done. Transfer to a serving bowl and serve with jasmine rice.

Here’s an end-to-end video of the whole cooking process.

Enjoy.

Green Thai chillies are notoriously difficult to find, even at the speciality supermarkets I listed in this post. Long green chillies, or jalapenos aren’t a great subsitute for green thai chillies (prik jinda or prik kee nu; sometimes generalised under the term ‘birdseye chilli’), as the the level of heat is very different and they don’t offer the essential floral fragrance these chillies provide. Thankfully, Nature’s Pride, a Dutch fruit and veg company, offer a bag of mixed red and green Thai chillies and they seem to be widely stocked at greengrocers all over London. See here for an image of the packaging - you’re probably familiar with it already if you live in the UK.

Also known as kaffir lime.

I’ve found it’s best to buy coconuts from Morrisons, Aldi or Sainsbury's rather than independent green grocers. The reason being is coconuts are perishable. Over time they ferment and go rancid. The only way to determine whether a coconut is off is to break it open and smell it. If it smells sweet and coconutty, you’re all good. If it smells like ethanol, it’s rotten and should be thrown out.

Coconuts from the big supermarket chains are almost always fresh; my guess is they benefit from the stricter regulatory practices mandated by these companies. Whereas the vast majority of coconuts I have bought from greengrocers have turned out to be rancid. They’ve likely been sitting, unbought, for months. Also - make sure you buy old coconuts (the ones with the hair on the outside) and not young coconuts which are sometimes sold at Asian grocers primarily as a drink - i.e. the juice inside them.